My Grandparents Were Sharecroppers

And both my parents picked cotton as kids. The legacy of slavery is more recent than you think.

About a week ago I found myself explaining, twice, how my sisters are I were the first generation out of picking cotton for both sides of our families. This was shocking for those I recounted it to — one a Black woman whose family had migrated north in the 1920s, and another my therapist, a white woman. In both cases, there was the shared horror of how the shadow of slavery was much more real and recent for my family than others.

Sharecropping, for those too lazy to google, was basically a type of totally messed up indentured servitude that happened after slavery ended where many former slaves went back to work for some of the same people who once enslaved them — usually for pennies or tens of cents — and lived in constant debt since they still lived in the same former slave quarters (but now had to pay “rent”) and often bought their food and supplies from, you guessed it, the same former slave owners, on credit.

The Substack of the Writer Formally Known As The Black Snob is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

This system trapped countless Black people in cycles of poverty, including my ancestors, and for my mom’s family, that cycle was not broken until my grandparents, along with their 9 children — my mother, aunt, and uncles as kids — all saved, worked and fought their way out of it as a team. My mother was put to work at 6, caring for her younger siblings, and when she was old enough, she and her brothers helped their mother get the cotton crop in while their father, my grandfather, took a side job working at an oil mill in Arkansas. This was a job the white family they worked for was initially against as they “feared” my family wouldn’t get their portion of the crop in on time. My grandparents assured this man they could do it — and they had 9 kids to help.

And this was all going on in the backdrop of the 1950s and 60s.

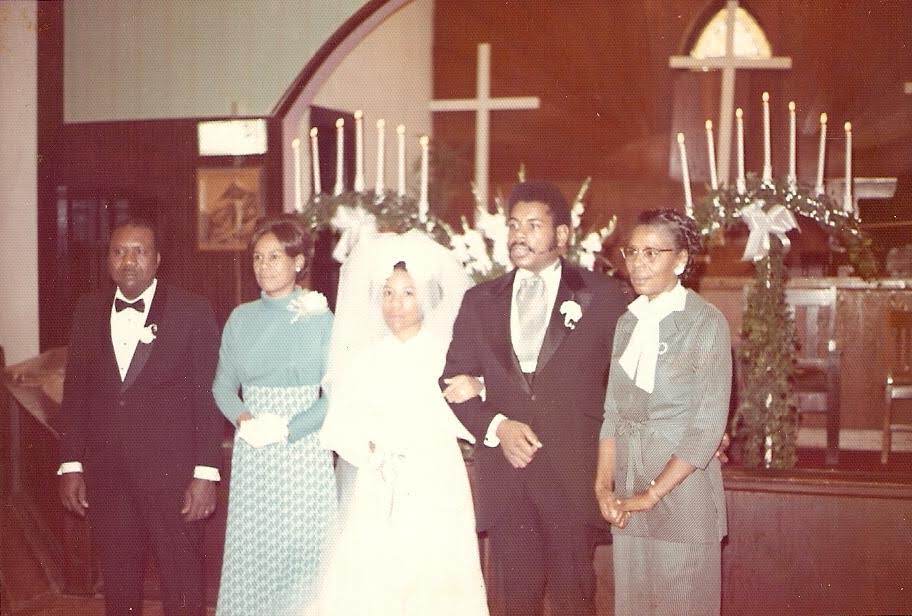

My mom fought her way out of the field and into college, then to a low-earning job as a school teacher in Iowa in 1968. She was still paying off her student loans from Philander-Smith, an HBCU in Little Rock, Ark. when she met my dad in the early 70s. She had followed a friend to St. Louis to take another teaching gig when they met. My father made so much more money than her as an engineer for McDonnell Douglas that he simply paid off the remainder of her loan after they married.

My father’s family was also poor, but not as poor as my mom’s family. They owned the land their house was on. His mother was a domestic worker and his father was a baker, among many other odd jobs. My father, who had been working since he was about 5 or 6, was allowed to keep the money he earned selling the local Black newspaper to use towards the things his parents couldn’t afford for him, which was the big difference between them. (Also, my dad was only 1 of 3 children as opposed to 1 of 9.) My dad found himself picking cotton as a side hustle dreamed up by his dad, but he was repulsed by it — both by the conditions (everyone had to drink out of the same barrel and ladle even though some of the adults had been “dipping snuff” and their backwash kept getting into the pot) and by the ridiculous amounts of cotton my grandfather expected his son to pick.

Thankfully, in the end, my father got out of the cotton-picking gig to devote most of his free time to his own endeavors, schooling, adventures, and odd jobs. He did have an actual childhood of playtime, friends, imagination, and pets. My mom was not so lucky, as she had so many siblings to care for while her mother worked in the field. She was so traumatized by the poverty she endured that up until she got sick in 2013 she struggled to spend more than $10 on any article of clothing, wouldn’t buy herself a proper coat because they were “too expensive,” and would often become irrational at the mere mention of money. She never wanted to know how much my father made. She never wanted to make a decision involving money. She only knew one thing — she was never going to be broke again and we kids were not going to “make her broke.”

As I told this to these two individuals, I fielded their questions and watched their horror grow. Me, I’m kind of numb to it, as my parents were both very open and honest about what they endured as children and young adults. I heard the stories from a young age well into adulthood. My mother even took us all as kids to the rundown, four-room shack she had grown up in off the plantation in Shoffner, Ark.

Plus, in St. Louis, their story was hardly shocking or rare, as the city was full of recent transplants from the South when I was a child — mostly from Tennessee, Arkansas, and Mississippi. And all of us spent our summers visiting the South to see our relatives. My dad and his brother were the odd outliers from Texas, a state where most Black people who left it migrated west, typically to California.

To the “slavery was a long time ago crowd,” it really wasn’t. Do you know who was born a slave in my family? My grandmother’s father. Do you know who was still alive up until a few years ago? My grandmother, the daughter of a slave, who died at 93 in 2021. People joke about “picking cotton” as if everyone stopped doing this once slavery ended, but, again, my father — who is still very much alive at 81 — did it. My mother, who died from complications related to her dementia in 2018, did it. My uncles, most of whom are still alive, did it. When I saw the heartwarming video of Halle Bailey’s grandfather being emotional over his granddaughter being the star of The Little Mermaid and how he was the son of a man who picked cotton, I was happy for them, but kind of numb because I wish my family had been able to escape their cycle of poverty sooner than … essentially five minutes ago … instead of countless relatives acting out every line the Langston Hughes poem “Harlem,” aka “A Raisin in the Sun,” aka “…. what happens to a dream deferred?”

Many of my grandmother’s siblings watched their dreams for a better life diminish and die at the hands of discrimination and the poverty they endured. Many of my relatives — most quite bright, quick-witted, funny, and talented — upon the realization that they were caught in a trap designed to keep them in poverty, turned to alcoholism to cope. My parents, along with one great aunt on my mother’s side of the family, were among the few on both sides to go to college and finally break the cycle through education. And my grandparents on my mom’s side did eventually get out of sharecropping and into homeownership in Newport, Ark.

Growing up, the racism that my parents had to overcome seemed so mountainous, that I became obsessed with (and admired greatly) some of my dad’s extended family who had made it out of that cycle and into home ownership in Santa Barbara, Calif. and, later, Junction City, KS, mostly by being better educated. (Most made it to at least an 8th-grade education, which was often as far as most poor, Black people could go in those days.) Plus, they married “well” in that the girls married military men who fought as Buffalo Soldiers in the U.S. military.

Again, my father’s aunts, in this case, were all smart, funny, kind, and quick-witted. I was fortunate enough to know many of my great-aunts and great-great-aunts on my father’s side, and I adored them all, from my Aunt “Dinky” who could do almost any voice and would pretend to be Tweety Bird when she’d call on the phone, to my Aunt Bert who always had a bit of an edge.

But at the end of the day, on both sides of the family, they were all just rural farm folk. Some did well. Most did not. Neither of my grandfathers could read or write because they had to be pulled out of school and put to work at a young age to help their families.

I don’t know what would have happened to me if I’d been born in the 1940s like my parents and other relatives instead of the 1970s. I was ambitious from the jump as a kid, always trying to read more books than my eldest sister and get better grades than the other kids I went to school with. It was like every bit of my ancestors was in me, everyone who watched their dreams dry up, sag like a heavy load or explode, propelling me forward. In my playtime as a kid, I dreamed of being on The Arsenio Hall Show or 60 Minutes as a correspondent. I fantasized about writing books and living in the “big city,” as suburban St. Louis was a bit of a drag for me. But the only thing standing in the way of success was often myself (and sometimes my mother’s Jim Crow-induced pessimism).

Racism (or sexism) would pop up from time to time, usually in the form of a racist teacher who would conveniently “lose” my homework assignments, but it couldn’t stop me now as it had historically stopped so many others in my family. Mostly because 1) my mother was a former school teacher who could not be fooled by the racists in our school district. She knew how the system worked and used this to her — and her kids’ — advantage. And 2) both my parents were college educated and became affluent in time. My mother was a stay-at-home mom back when that most definitely was not a thing for most Black women, so she was fully devoted to my education and success. Plus both parents knew the importance of education and saved up enough money to put us all through college debt-free.

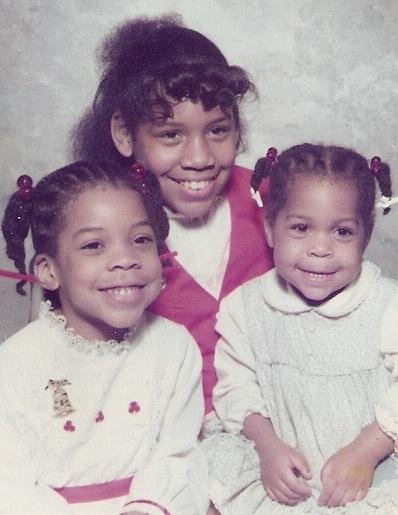

The end result was three daughters, all college educated, two who have owned homes, who all work in upper management. One sister is a vice president of finance for a nonprofit, another has an MBA and works in health care. I’m editor-in-chief of one of the leading digital news publications in HuffPost. Needless to say, our equally ambitious grandmother, who lived to see us all make it this far, was beyond proud. In fact, she was so proud, all her complaints about us were complete nonsense. She often asked me why I didn’t “have my own TV show” so she could “watch me on TV all the time,” and once harangued me for not “marrying Barack Obama” which was, by far, the weirdest conversation I ever had with her. Yet, it was actually quite sweet in that she thought so highly of me that she believed I should be the first Black First Lady of the United States. She just kind of ignored the huge age difference between me and the former president.

(I was 12 when Barack and Michelle met. Let’s just say, I never had a chance there, Granny!)

In my ambition, I had a similar mentality to my father who often talks about how he went into every raise and promotion negotiation with the attitude that the money he was asking for wasn’t just for him and his young family but for his mother and father and everyone he loved who was never compensated fairly for their hard work thanks to racism. Basically, his own personal reparations for the Belton clan.

As I climbed the journalism ladder, I was determined to try to help as many people as I could along the way, believing I had to give back or at least try to level the playing field for so many still being held back by discrimination, racism, and misogynoir. I had, after all, kind of won the genetic lottery by being born in 1977 to the parents I had and growing up as a “County Brownie” aka “Cosby Kid” in the 80s and 90s. Kids at school used to call my family The Huxtables as a joke for how “picture perfect” we seemed.

We were not. But that’s beside the point. My biggest beefs with my parents were that they were overprotective, controlling, and sometimes ignored my feelings, and that resulted in various disasters and traumas that I’m still unraveling in adulthood. But I’d rather have “childhood emotional neglect” than actual abject poverty, outward racial hostility, and being put to work when I should have been in preschool.

So, it’s fine.

It’s not fine though. But, really, it’s fine.

But not the sharecropping post-slavery until the 1960s part. That part is messed up.

And always will be.

The Substack of the Writer Formally Known As The Black Snob is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.