Confessions of A Friendless Gifted and Talented Kid

Being a Black "nerd" in the 80s was bad, but you know what's way worse? Racism.

In 1985, when I was around 8 years old, I begged my mother to let me apply for my school district’s gifted and talented program, even though she initially didn’t want me to do it.

Not because she didn’t believe I was “gifted” or “talented.” I was already winning awards in school and in the district for my writing and art, and I was a nearly straight-A student. (I’m probably the only child in the history of elementary school that couldn’t get better than a B in gym no matter what I did.) I was front and center in every school play or program. I played classical piano by ear and was writing short stories and poems for fun that I would illustrate with my art. No, the problem wasn’t me. It was “racism.”

The Substack of the Writer Formally Known As The Black Snob is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

There weren’t many Black children at the time in the district’s program, and she was convinced I would be barred from getting in somehow. But my mom, while a pessimist at times when it came to racist obstacles, had already taught me the better lesson — that you don’t let racism stop you from anything. She taught me this by teaching me my history, Black history, from a young age. And hearing the stories of resilience from people who faced much more adversity than me — being born slaves, or living during the time of lynchings and when Black towns would be razed to the ground over slights or lies — told me that racism was an unfair and atrocious obstacle but not an impossible one. Even my own parents were contradictions of my mom’s pessimism considering they both survived Jim Crow-era poverty and discrimination to now live in St. Louis as college-educated homeowners with three kids and an upper-middle-class lifestyle. Even at 8, I knew she simply was afraid for me, but I was fearless when it came to my ambition, even at a young age.

So after some conversation, she decided to let me apply even though she felt I would be treated unfairly in the process.

At the time, I was attending one of the few majority Black elementary schools within what was a mostly white school district. Meaning that while all the students save a handful were Black, a majority of the teachers were not, and the administrators, some of who were Black, believed Black children needed “tough love” as opposed to … well, kindness, understanding, and nurturing.

That was for the white children at the other schools.

Our behavior was routinely pathologized and treated as if it were abnormal when nothing was ever out of the spectrum of what a kid under the age of 12 would do — like being unable to regulate your emotions or misbehaving when there was a substitute teacher. We were regularly told we were worthless, undisciplined, “bad,” unruly, violent, and not as smart, innocent, or as good as the white students at other schools.

Back in the early 1980s, my elementary school didn’t have any students in the gifted and talented program from any grades and we were not encouraged to apply by the administration. I can’t even remember how I found out about the program — likely my favorite teacher at the time, my second-grade instructor Mrs. Stephens, who was also African American, had pushed it.

When I began the process of applying, my guidance counselor at the time tried to talk me out of it. She literally told me the testing I would face would be “hard” and that I might not get in. I told her I still wanted to try anyway. I was given a battery of exams, most of them IQ tests that probably wouldn’t pass muster today, and if you asked my mom, she would say I was given more tests than other students were told to take. I never knew if that was true or not and I did not care. I was happy to take all those tests because I knew I could beat them. I’d never met an IQ or standardized test at that point that I could not demolish. I was a voracious reader who went to the public library every weekend and read everything I could get my hands on — from Peter Rabbit to factual and historical books about everything from dinosaurs to indigenous peoples. I’d been reading since I was about 4 and my mom, a former teacher, had more than prepared me for school. I was already far and away reading on a junior high/high school level in the second grade and was punching above my weight class in math.

So, to the surprise of my guidance counselor (and maybe my mom), I aced every test, with or without racism’s thumb on the scale, and I, along with one other girl from my class, was accepted into the program.

Young and naive, I was so excited to go, believing I would flourish being around other “smart” kids. I also had bought into the mythology my school administrators had taught me — that white children were nicer and better behaved than Black children, so you can probably figure out where this is about to go.

The other kids were a mishmash of junior racists and their cold-shoulder followers. Despite my best efforts, I had no friends in the program but the one other girl I was in it with, and that girl, at the time, had stopped even engaging with me at our elementary school due to my tragic “uncoolness” as a “teacher’s pet” and “nerd.” She only interacted with me in the gifted and talented program because nobody really talked to her there either.

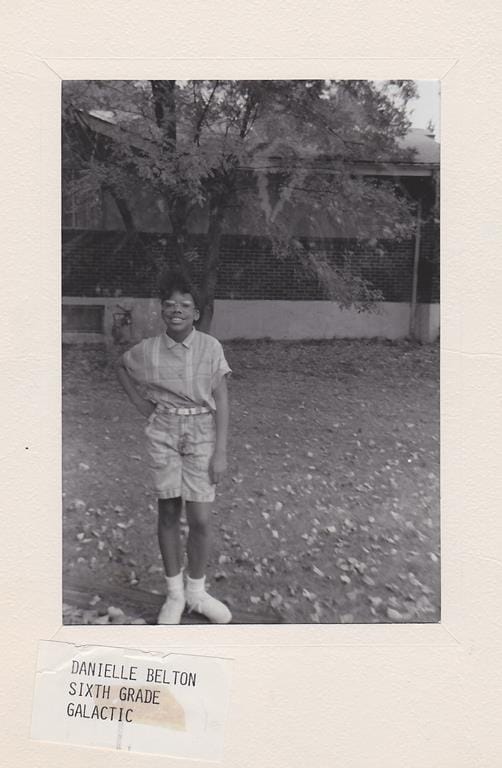

In gifted and talented, teachers would lose my homework and try to give me F’s. I would catch them doing this and they’d “apologize,” then smile passive-aggressively. The white girls remarked on my body and hair a lot — often negatively. I and the one other girl from my school ate lunch together, by ourselves. Even though I was able to hang all the way through sixth grade in it and made mostly As and Bs, I “tested out” of it when I got to junior high. It hurt my feelings, but not my ambition or spirit because I hated almost every minute of it due to how I was treated, but I was so proud to represent my elementary school and to prove so many wrong.

I knew I couldn’t be the first Black kid to go to an integrated, suburban school and have this experience. In fact, for those of us in similar situations, this was depressingly common. But despite my misery over being friendless in both gifted and talented and in my day-to-day at the elementary school, I was determined to not allow anything to stop me. I had big dreams and I was on a path to success and I did not care about what stood in my way. Even if it made me cry. Even if I felt “defeated,” I never was because I would always dry my tears and get to work.

Even though I’d been bullied from about the first grade until the fifth grade, by my final year in elementary school, something amazing happened. All my peers, many of whom I’d been in school with since pre-school, gave up on trying to make me feel bad. Maybe they matured. Maybe I matured. But the reality was, no one cared about picking on me anymore, as it wasn’t like I was ever going to change anything about myself for anyone, no matter how much they teased and mocked me. And because we were all Black, even when I was being picked on, they had always championed and admired that I was so good in school, and had a mentality that it was “OK” for them to be horrendous dicks to me, but not anyone else from the outside.

My classmates, for what it’s worth, were proud when I got into the gifted and talented program. That a girl who “went to Keeven Elementary” in North St. Louis County made it in there. A girl from the school with the “bad” kids with the bad grades. A girl who was Black, like them, and would represent them well. They were a contradiction in that way, those kids, who made me cry so much and made me feel so isolated and alone, but would also have my back because, well, racism is bigger than all of us.

Even then, as kids, we knew that racism didn’t make sense and that it wasn’t fair how we were treated. So yeah, I was a brown-noser in their opinion who “acted white,” but all that went out the window when it was time for someone to represent our school.

This is why despite how traumatizing it was to be friendless for so long as a kid — basically from third grade until 10th I truly struggled with making and keeping friends — I’m not bitter. I came to understand that a lot of the pettiness and cruelty wasn’t about me. It was about their families and the teachers and how awful they made them feel all the time. They had it much harder than me in some aspects. I, at least, had the love and support of my family. They were dealing with some colorism, self-loathing hellscape where the biggest bullies were kids whose parents and relatives constantly made them feel less than because they were dark-skinned or didn’t have “good hair” or were “overweight” or, and this was their parents saying this, unattractive. Then there were all the latchkey kids whose parents were too busy working to focus on them, their schooling, or even their feelings.

A lot of the “mocking” I received sounded more like disappointment.

Once a popular girl in my class was irritated because my mother had come to the school to bring me my mittens before I went out to recess on a cold day. She remarked in a way that sounded like chiding but was actually sad. She looked at me derisively and said that if she’d forgotten her mittens her mother would have told her tough luck, bet you won’t forget them next time when your hands are cold. It wasn’t the “sick burn” she thought it was. And like most kids in my class, she loved my mother and knew she was a former educator-turned-stay-at-home mom. She, along with all the other kids would ask, constantly, when she would come to work at the school.

So yeah, the kids sometimes sucked who I went to school with. I got punched in the eye. People cursed me out. People pulled my hair. I got threatened just for “looking” at people, whether I was looking at them or not. I was called names. People iced me out. I had constant anxiety attacks that came in the form of stomach aches and was out sick, a lot, both from allergies and actual illnesses, but also because sometimes it was just too hard and my mom would feel so bad for me, she’d let me stay home.

But I forgave them because 1) they were kids and kids aren’t good at regulating complex emotions; and 2) by the sixth grade, I realized no one actually “hated” me. The real problem was the hatred that existed inside us all thanks to racism.

Because of that, I learned to never forget what the real problem is. That’s what my public school education taught me. Go past the goofs, the immaturity, and rudeness, and get to the root of it. Did everyone really hate me, or did they just hate the situation and, at times, themselves? Was I just collateral damage? After all, I wasn’t the only smart kid in my school, yet that’s how I was often treated. Like the exception. Like the bright light in a “dark” place. And that was incredibly wrong.

I couldn’t stay mad at my fellow victims of a racist, colorist, ignorant society, but I could stay mad at racism.

I don’t remember the name of not one racist kid who was mean to me. You know why? Because they didn’t matter. They were all faceless cartoon villains. They were all the same. I was either invisible or someone to attack. All their moves were predictable and there was no path to acceptance as there had been with my former Black classmates, so there was no point in even trying. There was no solidarity. It was just straight-up Hunger Games, all day, every day, and not everyone made it out safe. The school-to-prison pipeline was real as I watched so many of my peers — mostly Black boys, but some girls as well — get pushed out of school for simply being kids. Kids with struggles, but still kids, denied the same humanity as their white peers. By the time I got to high school, the contrasts were stark. For every kid who went the distance and graduated with me, there seemed to be another kid who was in a halfway house or forced into special education due to “disciplinary issues.” Then there were those who had to drop out because they’d gotten pregnant. And around my sophomore/junior year, we were told vice principals would no longer break up fights, but that the police would be called and kids would be arrested.

And they were, so I walked a fine line.

For my entire schooling, I was a “good” kid. I didn’t curse. I didn’t have sex. I didn’t party. I dressed “modestly.” I didn’t do drugs or drink. Not because I didn’t want to loosen up a bit, I used to beg my parents to be allowed to date, but it was a no-go. No, the real problem was I knew the path to victory was narrow. If I wanted to make it out of this racist system alive, I had to be the best. All of America is just a series of traps for Black people. If you do something, anything considered “out of pocket,” thanks to racism, you will get dealt with as harshly as possible with the punishment never fitting the perceived crime. It all just felt too risky to simply live my life. I was so focused on not falling into any traps, I didn’t curse until I was about 19, I graduated college early in three years at 21, I got married at 23 (divorced by 24), didn’t drink until I was about 25, and didn’t try marijuana until I was 36.

My first (and only tattoo)? I was 40. I still have no children and have not remarried.

But nobody should have to live like this! To basically never go out, never date, never party, never experiment, or “have fun” because you’re afraid the hammer will come down and you’ll end up “in the trap.” When other people in their 20s were out dating, having sex, getting drunk, and screwing up, I was working feverishly as a journalist in American “dust belt” towns, going in and out of mental hospitals. I lived my life cautiously because of what I’d experienced as a kid. The margin of error was just too slim for a Black person. No risk ever seemed worth it. Even at the expense of my own mental health.

Today, I am who I am. Which is pretty much the same person I was when I was around 10 years old back in 1987. That was the year I became “self-aware” and realized what kind of situation I was born into. To this day, one of my favorite hip-hop songs from the 90s is De La Soul’s “Stakes Is High” because it spoke so profoundly to the situation both I and so many other Black people were in. We are in a society where the odds are never in our favor and what you want you have to take. Good enough is never “good enough.” The aspiration is to perfection even if it’s unobtainable. We blame each other for things over which we have no control in our search for control, and we eat each other alive trying to get out of the situations we were born into. We are taught that life is a zero-sum, that there’s only one door, one way, one path, one shot, one opportunity for not just you, but the entire race. You’re only as good as your last hit and always as bad as your flop. And a flop is a sign of doom for us all. If one of us makes it, that one person ascends, maybe other opportunities for others will follow, but if you don’t, all Black people are damned for that failure whether it had anything to do with them or not. In America, we are not afforded the luxury of being individuals, we are “Black” with a capital B. We are a monolith even if we can’t agree on shit. We are bound together in exquisite joy and pain upon pain upon pain. It isn’t fair, but what’s the alternative? You can let the system beat you and succumb to the trap. You can fight the system, and still get swallowed whole. You can try to fix it, amend it, legislate it, take it to court, and demand that America live up to its founding principles by finally and truly applying them to all.

Or you can check out. Mentally, spiritually, physically. You can just decide to not deal.

Unfortunately, in America, you can check out anytime you like, but you can never leave. Even if you run away to Europe or Africa, it’s still inside of you. This thing that’s so hard to describe.

It’s the same thing that made kids act like they hated me. It’s the same thing that made those kids hate themselves. It’s the same thing that got me to where I am today. It’s a double-edged sword.

Because we live in the most powerful nation on earth, it affords great opportunity if it doesn’t crush you under the weight of that “greatness.” You can fly, if you’re Black, but not without compromise, not without conditions, not without sacrifices.

We all have to lose something in order to gain. Let’s just hope it’s not ourselves.

The Substack of the Writer Formally Known As The Black Snob is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.